- Jupiter's aurora lights, the most powerful in the solar system, are partly driven by moon volcanoes.

- Volcanic eruptions on Jupiter's moon Io send electrically charged lava plasma toward the planet's poles.

- The Hubble Space Telescope helped researchers track electric currents driving the aurora.

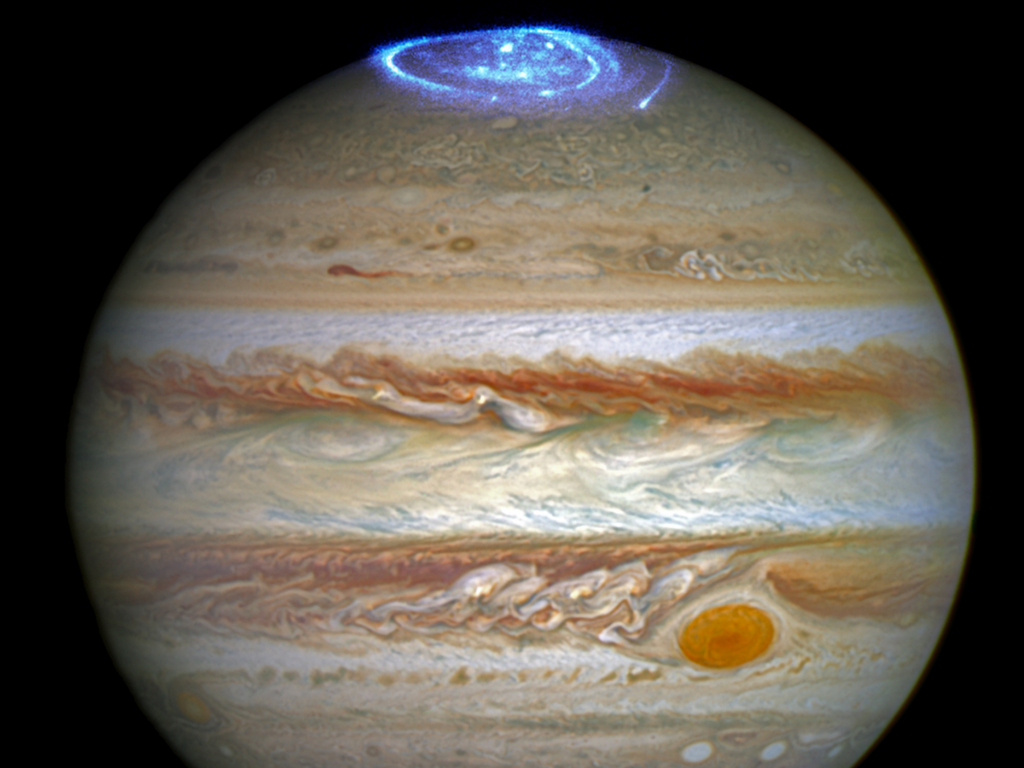

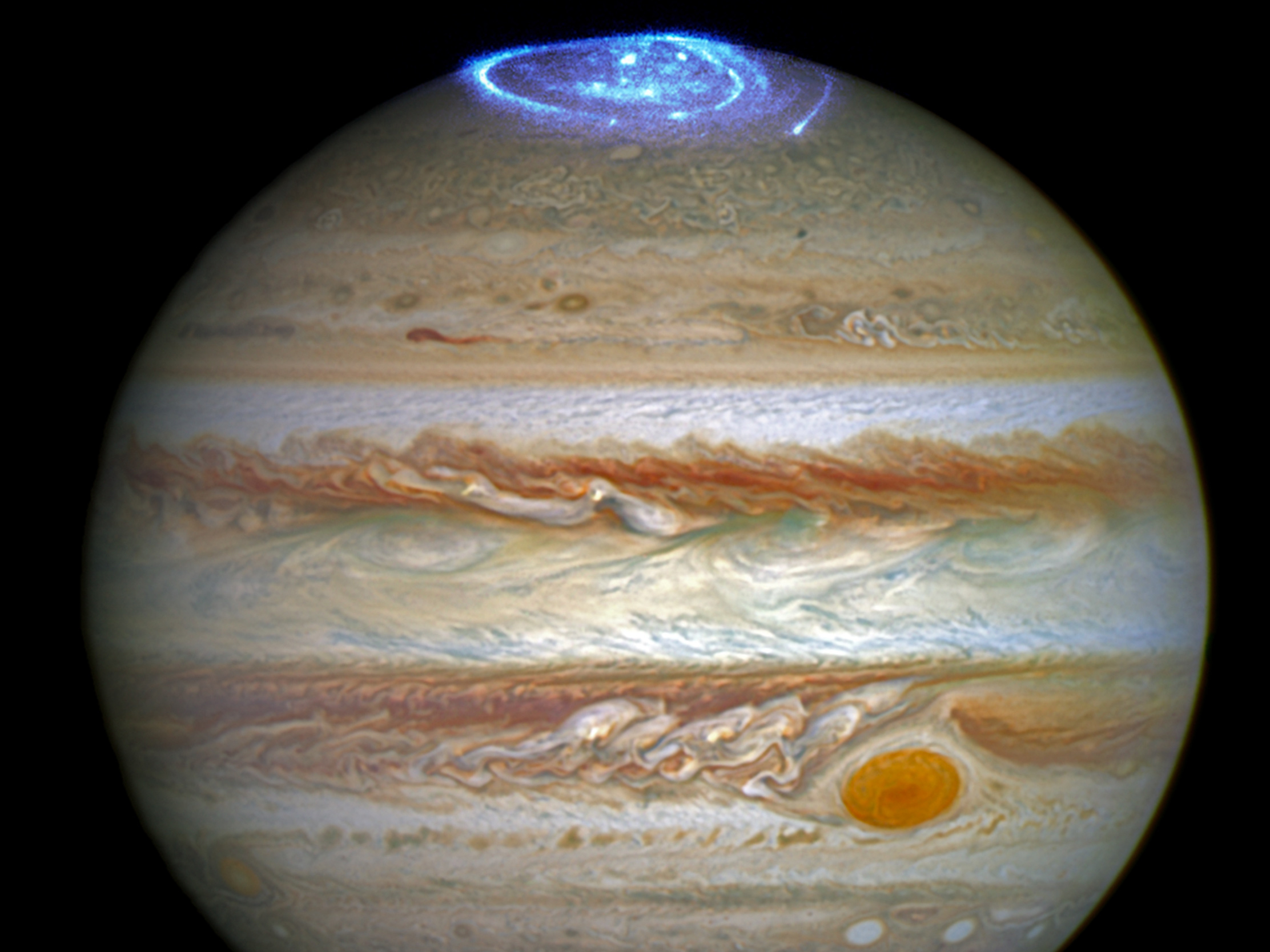

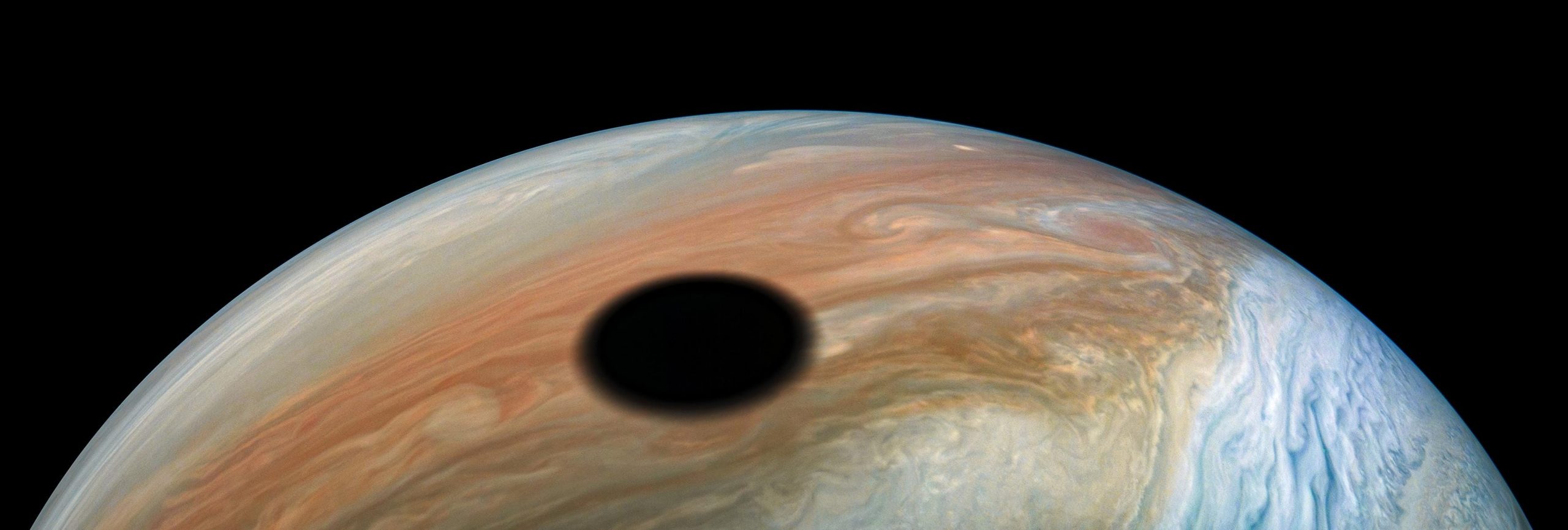

Jupiter's auroras — the lights that dance around its poles — are the most distinct in our solar system and over a thousand times brighter than Earth's aurora. Now, a new study confirms that these otherworldly polar lights come from a unique source: space lava.

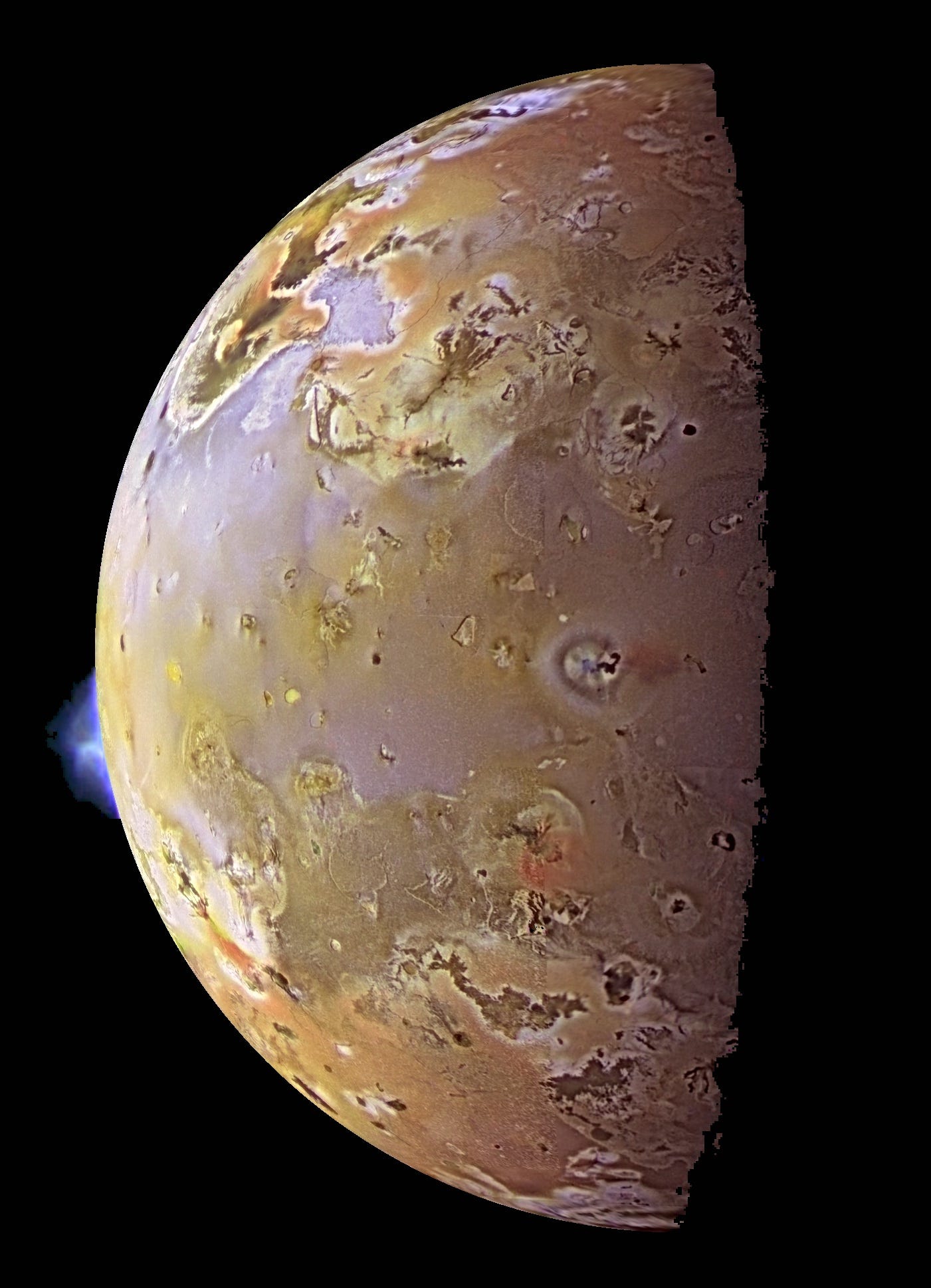

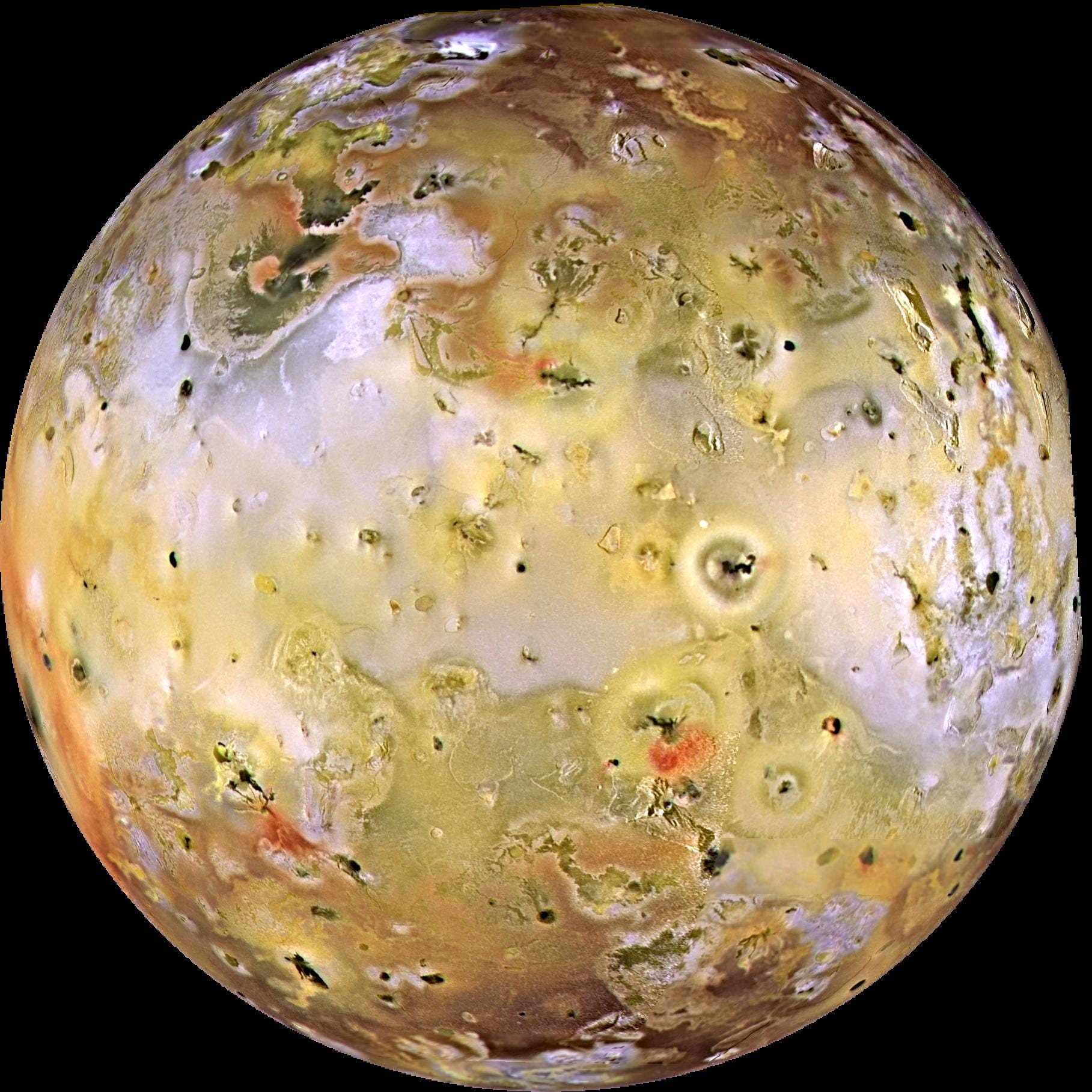

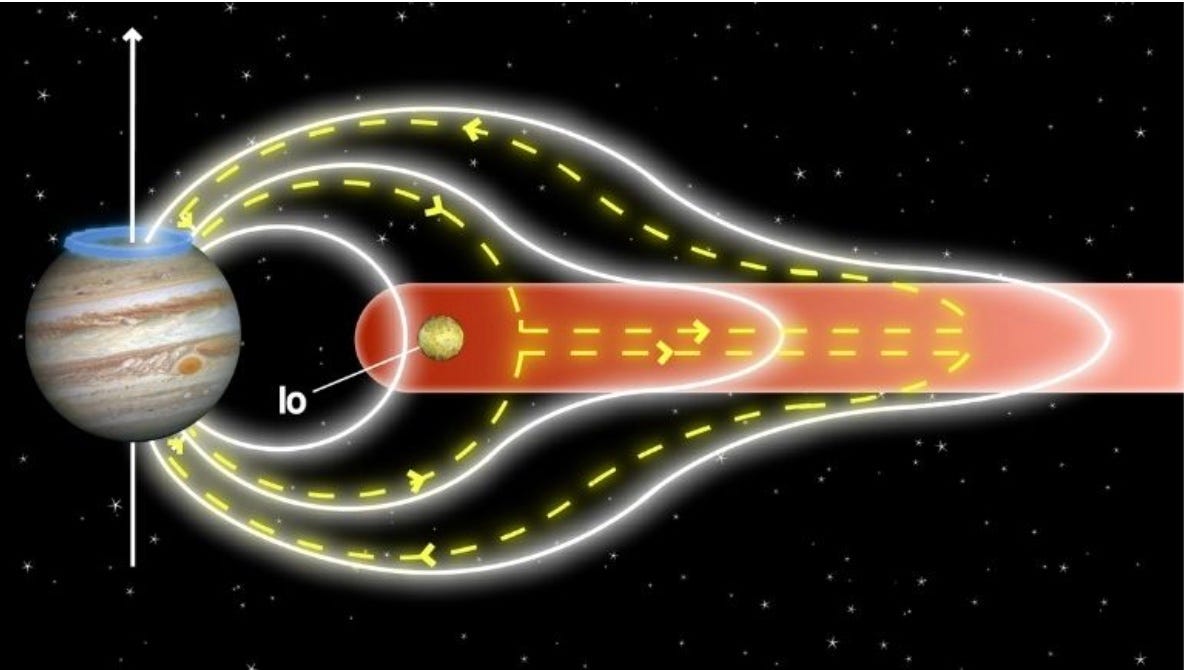

Jupiter's moon Io is the most volcanically active world in the solar system. Its more than 400 active volcanoes regularly shoot lava dozens of miles high, where it falls into Jupiter's orbit and becomes plasma — "a soup of electrically charged material," astronomer James O'Donoghue told Insider.

That space-lava-turned-plasma is then swept up in Jupiter's powerful magnetic field, which channels it to the planet's poles. There, the electrically charged particles interact with gases in the atmosphere to create aurora lights.

This was the reigning theory for two decades.

"The science was rather settled," said O'Donoghue, who studies giant planets' upper atmospheres at Japan's space agency, but was not involved in the new study.

NASA's Juno mission threw that theory into question once it arrived at the giant planet in 2016. The Jupiter-scouting spacecraft didn't find any signs of electric currents at the poles.

"It has been a tense few years in our community trying to figure out what is going on," O'Donoghue said.

Research published last month from the University of Leicester confirms the original theory and unites it with Juno's findings. Scientists gathered observations from the Hubble Space Telescope, which charted the brightness of Jupiter's auroras, and compared them with Juno measurements of the planet's magnetic field and electrical currents traveling through it.

"I nearly fell off my chair when I saw just how clear the connection is," Jonathan Nichols, an astronomer at the University of Leicester who lead the new study, said in a press release.

The results confirm the relationship between Io's volcanic eruptions, electrical currents in Jupiter's magnetic field, and the aurora — but the Juno measurements paint a more complicated picture than the initial theory.

Space lava takes a loop-the-loop ride around Jupiter

The study, published in the January edition of the Journal of Geophysical Research: Space Physics, describes the process as a tug-of-war between Jupiter's magnetic field and Io's space-lava plasma. Jupiter's magnetic field initially pushes the plasma away from the planet, but as the material travels further away, it can't orbit fast enough to maintain distance. Instead, it travels along Jupiter's magnetic field lines, back toward the planet's poles, cycling through Jupiter's upper atmosphere.

Other planets orbiting other stars — many of them similar to Jupiter — could have their own auroras. Their magnetic fields could behave in similar ways to Jupiter's.

Astronomers have observed auroras on seven planets in our own solar system. They seem to be common, but Jupiter's are exceptionally powerful, partially thanks to Io's volcanoes.

Juno, which is still flying around Jupiter and its moons, could tell scientists even more about the planet's stunning auroras.

As O'Donoghue put it, the relationship between Io's volcanoes and Jupiter's aurora "is one of the most fascinating aspects of the solar system."